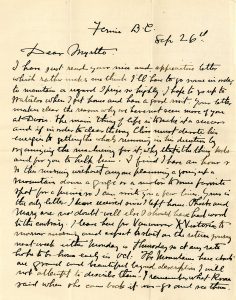

One of the tasks undertaken by researchers in a museum collection is the transcription of historic documents. Typing out old letters, diaries, and notes helps preserve their contents when paper tears and ink fades. Perhaps the biggest challenge in transcribing historic documents is deciphering the handwriting. The personal writing style and flourishes can be dauntingly incomprehensible to our twenty-first century eyes.

However, with time and practice, we can learn to read these documents. In many cases, it takes learning a specific writer’s hand, learning to recognize a particular squiggle of ink as a “P,” for example, not a “B.”

An unexpected challenge when deciphering these letters is the slang. Just as our language today is dotted with culturally relevant slang, idioms, and memes, so too was the language of the past. Language is always changing; as quickly as new idioms and slang become popular, the same fall out of use. As such, historical idioms and slang terms can prove to be quite challenging to understand since we don’t have the context that the writers had when writing. Homer Watson along with his friends and family used their fair share of slang in their writing, resulting in some fascinating turns of phrase to puzzle out. Here are some of our favourites:

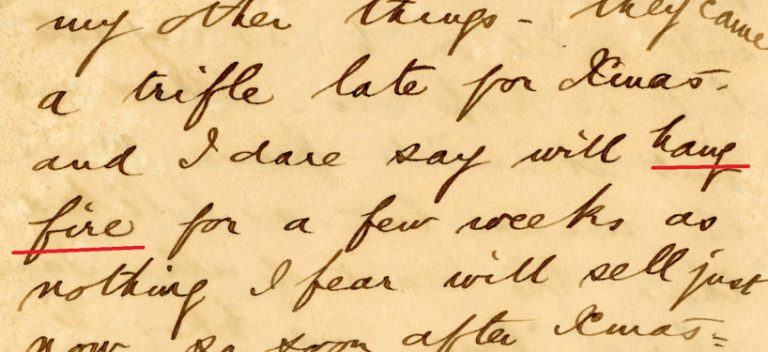

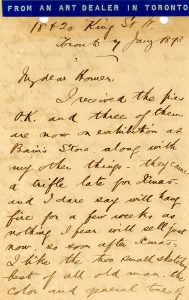

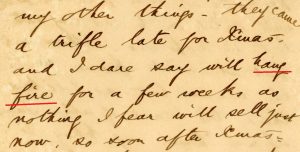

In 1893, John Payne, one of Watson’s art dealers, wrote informing him that his work would have to “hang fire” for a while, as his paintings arrived too late to sell for Christmas. The phrase “hang fire” or “hanging fire” originated around the eighteenth century when gunpowder was widely used in firearms. The term was coined to give a name to the way older muskets and guns would fail to fire properly because the gunpowder had not ignited, or took much longer to carry the ignition therefore delaying the charge. Over time, “hang fire” came to signify a delay, or a situation when nothing could be done but wait. Given the decline in the use of gunpowder rifles, it makes sense that such slang has fallen out of use. Amusingly, Payne also referred to Watson’s paintings as “pics” – an abbreviation we still use in reference to pictures.

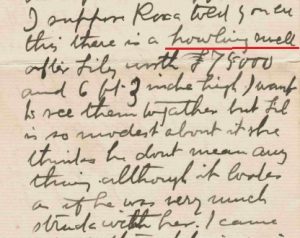

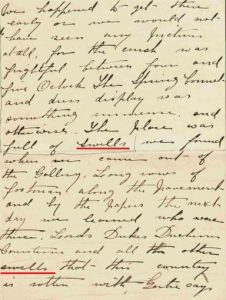

Both Roxa and Homer Watson wrote home to their family while travelling throughout England in the 1890s and early 1900s, often referring to a “howling swell”. At that time, “howling” was liberally used as an intensifying descriptor. When used in conjunction with “swell,” it expressed that the person in question was really a swell. In the late 1800s, “swell” most widely referred to an extravagantly well-dressed man. In fact, it seemed to denote an overdressed man, though very fashionably so. Most often definitions of this term, popular from the mid-1800s up until about 1910, apply it to either aristocrats or those posing as such. This seems to be how Homer and Roxa used it, referring to the wealthy or titled people they came across in England.

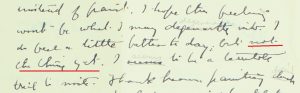

Another turn of phrase that appears within many of the archival documents at HWHG is “the thing”, or “not the thing.” On some occasions, Watson used this in reference to his health, indicating that he was not feeling well, however, the phrase has a number of meanings dependent on context. “Quite the thing”, as a colloquialism, dates to the late eighteenth century continuing into the twentieth. In its earlier use, “quite the thing” seems to refer to being suitable, respectable, or socially acceptable, “the thing” being what is right, proper, and fashionable. Homer’s use of the phrase in comparison its other uses and meanings illustrates how language can change and evolve over time.

While historical slang can sometimes throw the transcriber for a loop, it’s always fun to find it scattered throughout historic documents. These phrases and words enrich our understanding of historical writers as people and offer us greater insight into the social and cultural mores and mainstays of a given time. Understanding these terms can also help in the transcription process. The more familiar we become with common turns of phrase, the more easily we can pick them out and accurately transcribe them.