EXHIBITION

Many of Phoebe’s written works are still to be discovered. Hastily written on the back of letters and scrap paper, since paper was considered expensive and scarce at the time, many of her works are easily overlooked. With each discovery, the inner workings and character of this pioneering woman are revealed

Deeply interested in the advancements of medicine during her time, Phoebe recorded her ideas on maintaining a healthy lifestyle as well as her inventive treatments for corns and Rheumatic diseases.

She also utilised her creativity in her approach to medicine and was unafraid to express her individualistic opinions. This is demonstrated in her poem ‘With Apologies to Kipling’ (Watson, n.d.) which opposes the author Rudyard Kipling’s love for smoking.

Tobacco

By Rudyard Kipling, 1884Sweet is the Rose’s scent—Tobacco’s smell

Is sweeter; wherefore let me charge again.

Old blackened meerschaum, I have loved thee well

From youth, when smoke brought sickness in its train.Foolish I was: Manillas I disdained,

And cigarettes to Burmahs did prefer,

And even spumed Havana’s fragrant joy;

But now my mind is pained,

In that my smoking days I did defer,

Nor knew this pleasure when I was a boy.

Although smoking was a normal pastime during her life, enjoyed by her brother and peers, Phoebe was part of rising concern as new research began to reveal its impact on health.

Throughout her life, Phoebe taught students from Kitchener, Brantford, and Stratford. She also operated an art store in Galt between 1912-1918 where she offered classes in oil and watercolour painting and china painting. Based on descriptions of Phoebe’s personality, she was likely a firm, but encouraging teacher.

“…Candid and outspoken. She flatters none but never offers her praise or approval grudgingly”

-Doon and Blair Women’s Institute, 1984

During the summer, Phoebe travelled to her cottage in Oliphant, sometimes in the company of her students, to further immerse herself in nature. This display case contains sketches from her time in Oliphant, and her hand-painted china, alongside paintings and materials used by her students.

In 1902, Phoebe moved to Galt with her mother, Susan, and cared for her until her death in 1904. Freed from the responsibilities as her mother’s caretaker and living independently in her own home, Phoebe ventured into the retail business and operated an art store on Water St. N, Galt, between 1912-18. There she sold fancy goods and offered classes in painting and pyrography. Evidence also suggests that during this time Phoebe rented her home on Barrie St. to draughtsman, Ernest Newlan.

By 1918, after the death of Roxa, Homer’s wife, Phoebe closed her store and sold her property in Galt to return to Doon to care for her brother and niece. Although Phoebe’s time as an independent business owner was short-lived, she felt the occupation did not suit her and later commented she felt “years younger without all the worries and cares of business” (Watson, 1937).

The art world was a male-dominated scene during Phoebe’s lifetime. Like many women of her time, Phoebe turned to the craft of china-painting, as it was considered a socially acceptable profession for female artists.

Her biggest achievement was through her contribution of twelve soup plates to the Canadian Historical Dinner Service in 1898. These soup plates depicted scenes from across Canada, similar in style to plates seen in this case.

As the first curator of the Watson Art Gallery, Phoebe was responsible for tours, sales, and the upkeep of exhibition spaces. An excellent orator, Phoebe exuded old-world charm to hundreds of visitors. Her tours of the gallery used personal memories and first-hand knowledge to reveal details behind her work and Homer’s paintings.

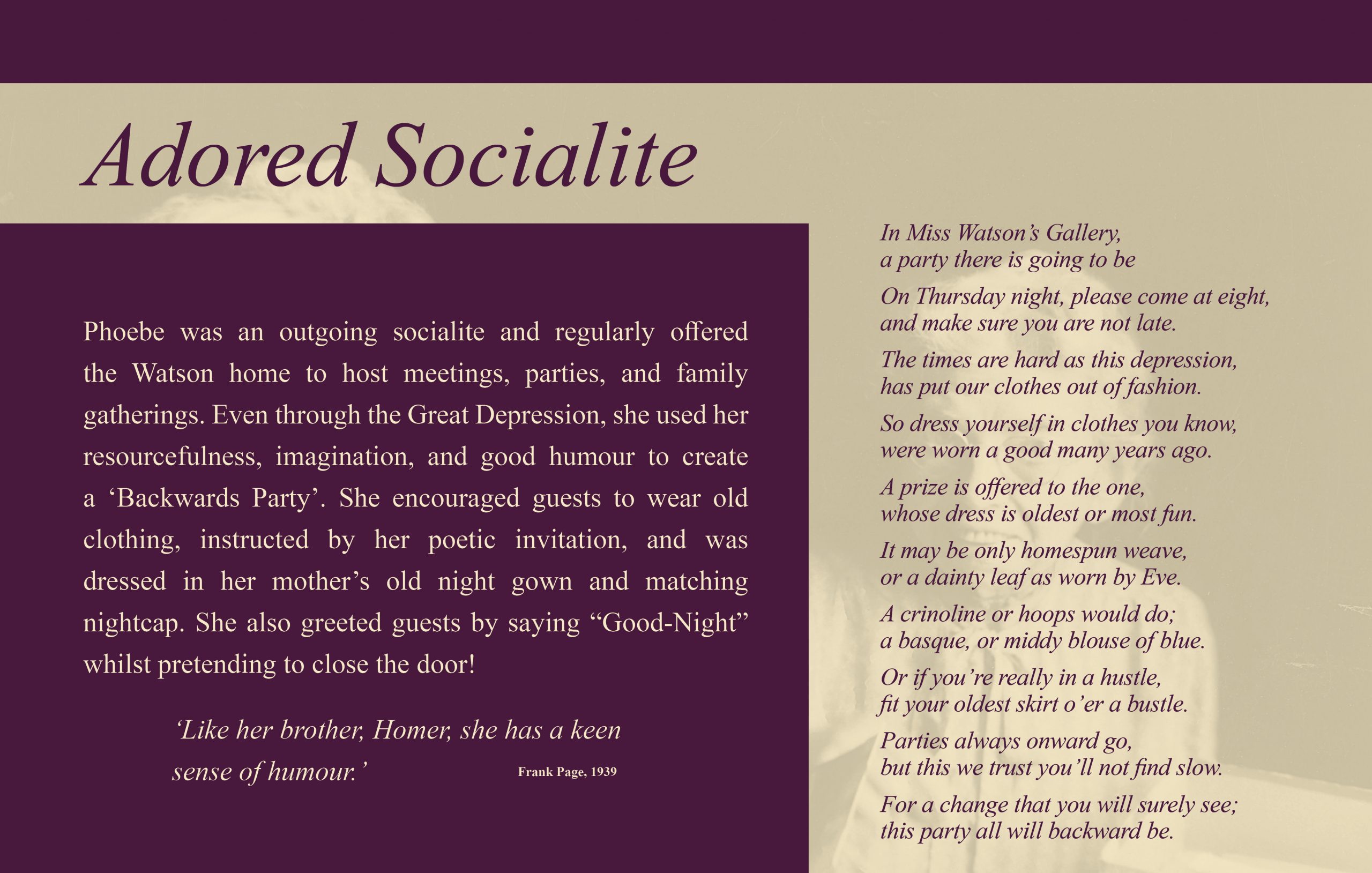

The following compliments filled the Gallery’s guest books as she was adored by locals and travellers alike for her expertise and lively character.

“It is very inspiring to meet someone at 87 with so much youth” – Laura B. Hodgins

“Though I have seen Homer Watson’s pictures, I have never enjoyed or learnt so much from his life as was revealed tonight by the pictures themselves and by his accomplished and talented sister, Miss Watson.” – Hugh P. MacLean

Phoebe Watson played an instrumental role in the local Ladies Aid organization, a society of women dedicated to charitable causes and providing financial assistance to the Doon Presbyterian Church. As one of the founding members of the Doon Ladies Aid, Phoebe served as President of the society for 14 consecutive years. During her Presidency, she was responsible for the successful organization of many fundraising and charitable initiatives.

The notebook to the left contains minutes of weekly meetings and details the planning and success of the 1934 Picture Exhibition and Bazaar at the Watson Art Gallery, followed by an educational visit of 50 children from Doon School.

“…Women’s influence on the world at large is always felt”

Phoebe Watson, 1915

Phoebe witnessed the growing push for change and the enfranchisement of women in Canada. Whilst Phoebe supported the cause, she also realised that it would spark change in the role of women. Contrary to reports on the social issue by newspapers at the time, Phoebe disagreed with the assumption that a woman’s time could be better utilised away from the roles of homemaker and mother. She argued that this view disregarded the hard work women do in the home and the long-lasting impact they have in raising future generations.

Homer Watson House Foundation Collection

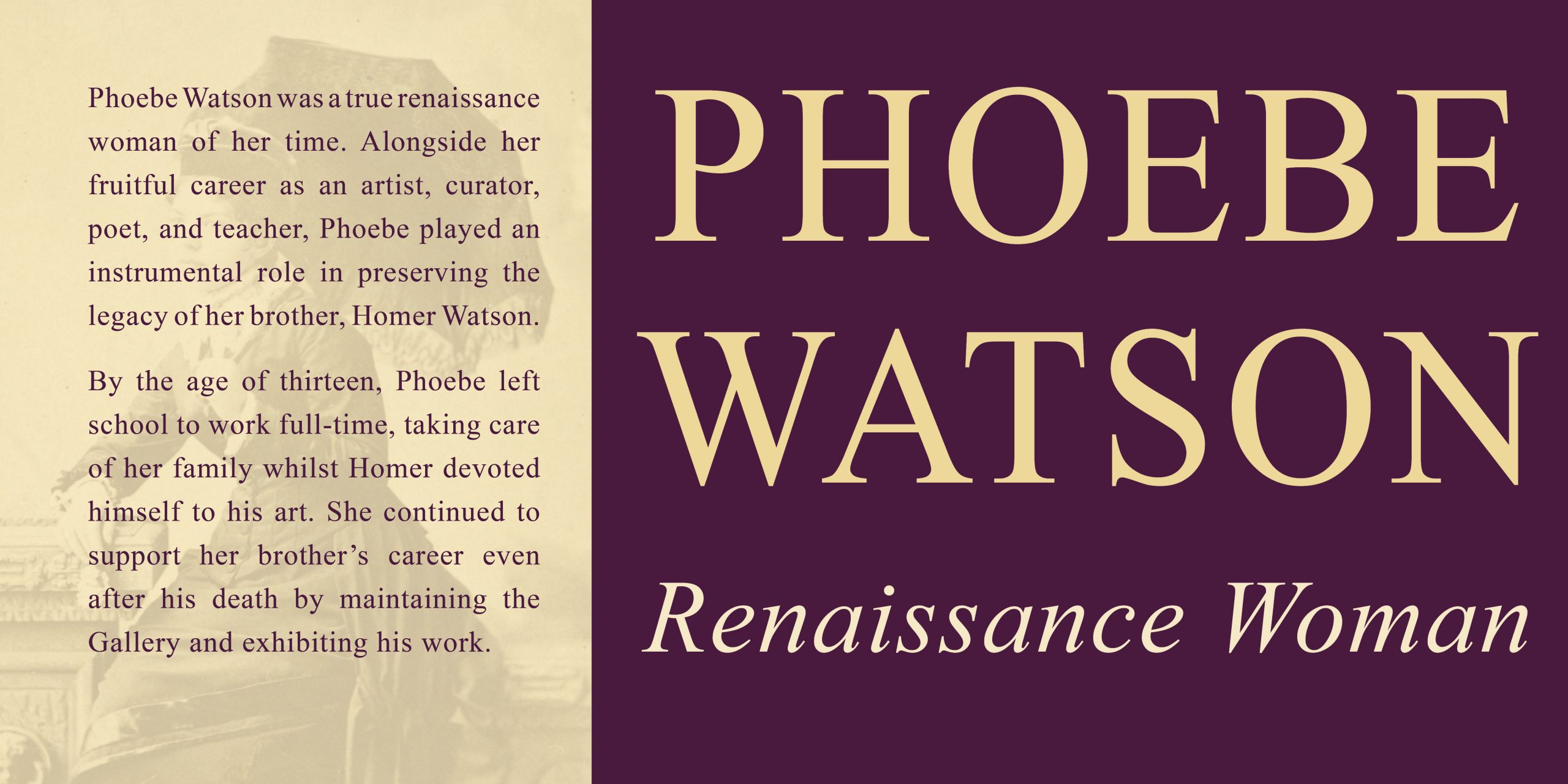

Phoebe demonstrated irrefutable loyalty and deep devotion to her brother throughout her life, From a young age, Phoebe worked as a mill store clerk and quit school to support her brother’s dreams to become an artist. Although it was common for unmarried women to work, local villagers criticized Homer for surrendering his role as the breadwinner to follow a precarious career as an artist. However, Phoebe was unapologetically outspoken and supportive of her brother. When confronted about her new job and responsibilities, she explained, “If it does not bother me, I cannot see why it should concern you.”

Throughout Homer’s life, Phoebe provided him with advice on how to improve his work, and sometimes even made corrections herself.

“When he[Homer] was at lunch that day, she returned to the studio to see what he had done to the picture and, observing a cow with one leg a bit too long, she picked up a brush and painted out the deformity, wondering how long Homer would be in the studio before discovering the change. Shortly after, Homer came in, and at the first glance at his canvas said, “It does look better doesn’t it?”’

– Frank Page, Artist and Man, 1939

She continued to “touch up” Homer’s paintings after his death in 1936 until he supposedly contacted her through a séance telling her to stop! Between Homer’s death in 1936 and her own in 1947, Phoebe continued to dedicate her time and efforts to protect the legacy of her brother through exhibitions, tours, and the conservation of his writings. However, the colossal task of protecting Homer’s legacy may have been beyond Phoebe’ capabilities and in 1944, an enquiry was lodged by Charlotte Whitton, the first female Mayor of Ottawa, regarding the safety of Homer’s etchings under Phoebe’s care as his work was damaged, possibly by fire.

‘Phoebe Watson is possessed of a fertile, keen, and cultured mind.’

-Frank Page, 1939

Homer Watson House Foundation Collection

Phoebe Watson expressed her individualistic thoughts on the changing world around her. Topics that frequently interested her were the limited support offered to Canadian artists, and the misconceived realities of the working class portrayed by newspapers.

The excerpt to the right, details Phoebe’s frustrations with the lack of financial support offered to struggling artists, as well as her innovative solution to form a guild or an association to support artists through grants.

“…why all artists, inventors, and literary people are poor, and why do not people of means see their need? And why do they not form some sort of guild to look into this matter and to provide a common fund where a man or woman so gifted, could draw on the funds until he could do his or her best work and there would be further need of its help? I am aware that there are scholarships to but how many people can even afford to go long enough to school to get them and at best they are only for the ones who learn by rote and not for the creator.”

Phoebe Watson, 1911